Welcome to the Impact newsletter — your guide to the feminist revolution. This week, we are paying tribute to Gisèle Pelicot, who has changed the way France talks about sexual violence forever. This edition is a little longer than our usual newsletters, we hope you will agree that the subject merits it. To stay up to date on all that’s making news in the world of gender equality, follow us on Instagram and LinkedIn. You can read this newsletter online here: http://lesglorieuses.fr/gisele-pelicot  Gisèle Pelicot has changed the world by Megan Clement I recently met with a friend, a fellow journalist, who had just returned from Avignon, where she was covering the trial of Dominique Pelicot and the 50 other men he is accused of inviting to rape his wife Gisèle Pelicot after having secretly sedated her. The most sinister thing about being there, the journalist told me, was that she never knew whether the men milling around her outside the courtroom were members of the press, members of the judiciary, administrative staff, part of the crowd of people who turned out each day to support Gisèle Pelicot or, you know, them. Was the man beside her a prison warden there to monitor the eighteen accused who are being held in custody, or the prison guard who has admitted to raping Gisèle Pelicot inside her home in November 2019? Was he a reporter covering the trial, or the local journalist who said he had taken Dominique Pelicot’s word that the sleeping woman he is shown on video raping had consented, and on whose laptop police found thousands of images of child sex abuse? Was he an IT technician making sure the systems in the courtroom weren’t overloaded by the hundreds of TV cameras set up to cover the trial, or the computer expert who asked Dominique to let him know when Gisèle was fully sedated because the car journey from his home to theirs would take him 20 minutes? I have been thinking about what my friend told me in the weeks since we met, wondering why this small detail taken from an enormous, unprecedented trial that has laid bare some of the most horrific accounts of mass rape this country has ever heard, bothered me so much. Then I realised. The discomfort she felt in that foyer in Avignon, not knowing which of the men around her had raped an unconscious woman, is not exceptional. Rather, it is an accurate representation of the world we live in. To put it another way: we are all in that courtroom, all the time. We never know if the people around us have histories of sexual violence, whether they would do what as many as 80 men are believed to have done to Gisèle Pelicot, given the chance – whether they already have. This is the reality we are forced to accept in order to live.

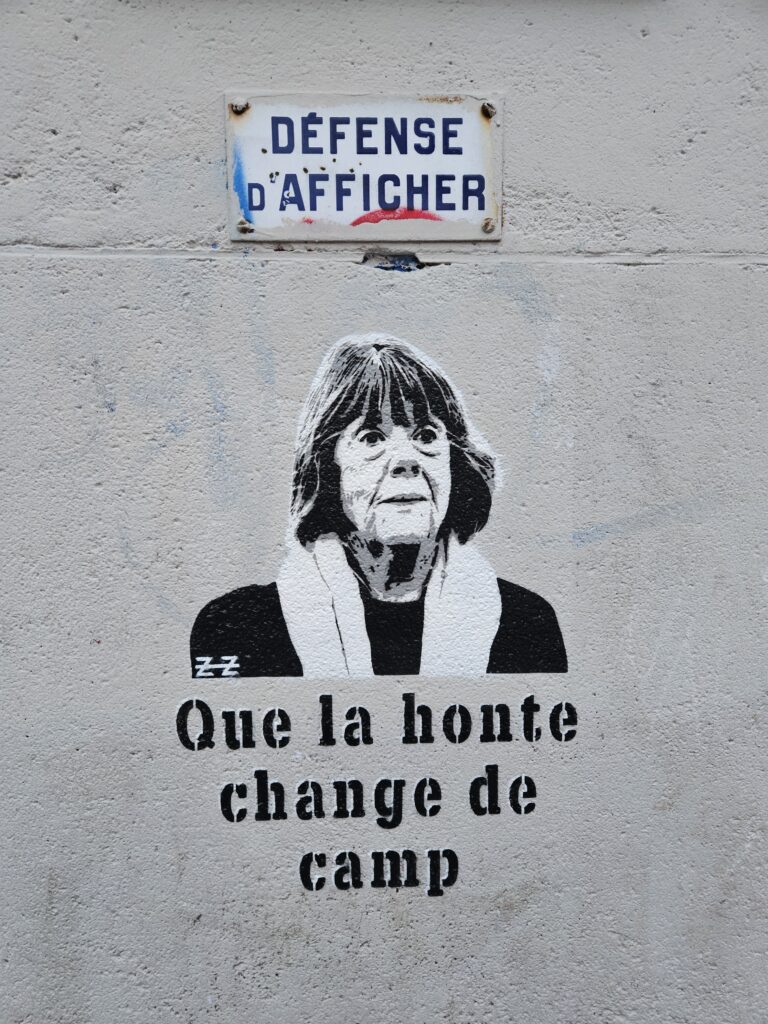

There are more than 400 rapes or attempted rapes every day in France, a country where the vast majority of sexual assault charges are dropped, and where survivors are often sued for defamation if they speak out about what happened to them. This is a nation where rape is a given and rapists are hidden by design. In fact what is truly exceptional about the Mazan rape trial is that it is happening at all. In France, 94% of rape cases are abandoned by prosecutors before a trial can take place, a figure that only accounts for the 6% of sexual assaults that are reported to the police in the first place. If Dominique Pelicot and his co-accused are convicted, they will be in the significant minority of rapists. The under-reporting of sexual violence makes it hard to estimate how may rapists are actually condemned for their crimes, but we know that only 15% of the tiny number of cases that are registered by police result in a conviction. The accused in the Mazan rape trial acted with impunity because they live in a world that tells them they have it. What will it take to change this status quo, which so drastically favours the rapist over the victim? The answer may be Gisèle Pelicot herself. Over the long months of this devastating trial, this 72-year-old former logistics manager has become one of the most effective feminist communicators the world has ever seen. The shame must change sidesWe did not want to look at the Mazan rape trial. When the facts were first revealed, the number of perpetrators, the systematic methods of Dominique Pelicot, the depravity of it, the enormous reach of it seemed too grotesque to even consider. We turned away. Paradoxically, the very ordinariness of the crimes made it equally hard to bear. We are most at risk of sexual violence from someone we know, and so it was for Gisèle Pelicot, whose husband is accused of orchestrating her mass rape. The most dangerous place for a woman is inside her own home, and so it was for Gisèle Pelicot. There is no single profile of a perpetrator, and so the accused represent a cross-section of the society we live in: young, old, employed, unemployed, single, married. Fire-fighters, pharmacists, shopkeepers, lorry drivers, business owners, plumbers, delivery drivers. Thirty-seven fathers are on trial for the rape of Gisèle Pelicot. There are no monsters, only our neighbours, our families, our communities. It is easier to get through the day if we do not think about these things, though we know them to be true. Many of us avoided the news because we didn’t want to hear about what had happened to Gisèle Pelicot. But Gisèle Pelicot wanted us to pay attention. Would she have a closed trial? She would not. Would she change her name to distance herself from her husband? She would not. Would she block the videos of her rapes being shown in court? She would not. Because she had done nothing wrong, and she wanted everyone to know that. Her repeated declaration: « The shame must change sides. » As the journalist Virginie Cresci writes: “Rape is not a natural disaster. Rape is a crime: a deliberate, intentional act, the exercise of violence in its greatest cruelty. The closed trials in which it is exercised renders it invisible and limits our collective understanding about its magnitude and the considerable damage it causes.” By asking for an open trial, Gisèle Pelicot showed that processes that purport to protect victims of sexual violence can actually harm them by hiding the pernicious banality of rape. It is one thing to say that victims of sexual violence should not be ashamed, and that perpetrators should be. It is quite another to prove that by allowing videos of that violence to be shown to the world’s media, and to sit in the same courtroom while it happens. Gisèle Pelicot did not just say that the shame should change sides; she flipped the script herself, and she gave permission to others to do the same. “I want victims of rapes to tell themselves, ‘If Ms Pelicot did it, we can do it too,’” she told the court. Photo: Annette Young, France 24 Beyond #MeTooThanks to this trial, concepts like “rape culture” that were previously confined to discussions between feminists are entering the mainstream. And there is preliminary evidence to suggest that Gisèle Pelicot has changed attitudes in a way that feminists have been trying to achieve for decades. Data from the polling group Ifop shows that three-quarters of French people believe the trial has revealed how normalised and widespread sexual violence is in France. One of the biggest challenges of feminism is to encourage men to reflect on their behaviour and the advantages patriarchy bestows upon them. According to Ifop, more than half of male respondents agreed that all men bear some responsibility or guilt for cases of sexual violence in light of the Pelicot case. This turnaround in attitudes is all the more remarkable given the notoriously lukewarm reaction to #MeToo in France. In 2018, one hundred French women signed a public letter denouncing the perceived excesses of the 21st century’s largest mobilisation against sexual violence. Rokhaya Diallo has written that “the signatories, including such illustrious artists and French intellectuals as Catherine Deneuve, placed France in a singular position: that of a country that places its Casanova culture above women’s safety.” Before #MeToo, the most high-profile sexual violence case France had known this century was that of Nafissatou Diallo, the hotel cleaner who accused Dominique Strauss-Kahn of rape in a New York hotel room in 2011. Despite a wealth of physical evidence supporting her version of events, the case in New York collapsed on the basis that she lacked “credibility”. She was a young Guinean refugee with limited English, a working-class single mother; he was one of the most powerful men on the planet. Credibility is always relative. In France, Nafissatou Diallo was accused of hallucinating, of trying to bring down the next president, despite the women who subsequently came forward with their own stories of Strauss-Khan’s sexual misconduct. After #MeToo, many women have shared their experiences, knowing that speaking out against sexual violence and incest will lead to some people believing them – usually feminists – but at least as many accusing them of lying, of jealousy, of improper motives: Sandrine Rousseau, Vanessa Springora, Adèle Haenel, Judith Godrèche, there are too many to mention them all. Some have been sued for defamation for speaking up. It does not take away from Gisèle Pelicot’s courage and dignity to ask why she has received such an outpouring of public support while the women who came before her were greeted with suspicion and defensiveness. One reason is the unusual amount of evidence against the perpetrators of these acts — hours of video footage filmed by Dominique Pelicot and kept on his laptop, only to be discovered by police when he was arrested for filming up women’s skirts in the supermarket (a reminder that sexual harassment is rarely an isolated incident, and that contrary to the views of the signatories of the public letter, is often linked to much more serious acts of violence, including rape). But this is not the whole story. We must ask why we have been more prepared to listen to Gisèle Pelicot than other survivors who have carried the same message over the years. Because she is older, white, softly spoken, and lives outside the big city? Because the accused in this case are not powerful men, so she is not seen as inherently suspicious? Because she was unconscious during the rapes, so she can’t be accused of not fighting back hard enough? Even then, she has been asked by defence lawyers if she was an “exhibtionist”, or whether she was conspiring with her husband to bring down his 50 co-accused. Some people will never let the truth get in the way of blaming the victim. Gisèle Pelicot knew that she had the chance to advance an important public discussion about sexual violence in France. She has used her platform to thank feminist campaigners and to share what they have been saying for decades with a wider, newly receptive audience. To continue her legacy, the challenge will be to ensure that the shame changes sides even in cases of « imperfect » victims or high-profile perpetrators. Spain’s « La Manada » case changed the country’s rape laws. Photo: Marilín Gonzalo. CC BY-SA 4.0 Consent and the lawThe greatest hope of a widely covered trial like this is that it will lead to a change in law, that the balance will tip away from impunity and towards justice. We know from events in Spain that a highly publicised rape case can lead a country to revisit how it treats sexual violence. The “La Manada” rape case saw five men who had filmed themselves gang-raping an 18-year-old woman in Pamplona convicted on a lesser charge of “sexual abuse” because the crime of sexual assault required “violence” or “intimidation” on behalf of the perpetrator. The victim’s perceived passivity led the court to find that violence and intimidation were absent. Thousands of protesters flooded the streets in response, demanding justice, and in 2019 the charges were upgraded to rape. In 2022, Spain passed an “only yes means yes” law, which requires affirmative consent. Despite being a signatory to the Istanbul Convention on preventing and combating violence against women, which includes consent in its definition of rape, the law in France requires an assault to contain “violence, constraint, threat or surprise” to be qualified as rape. Just last year, France joined with Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic to block attempts to establish an EU-wide definition of rape that included the notion of consent. It is a testament to the power of Gisèle Pelicot’s advocacy that nine out of ten French people support the introduction of a consent-based rape law. Before the vote of no confidence that led to the fall of Michel Barnier’s short-lived government, both he and justice minister Didier Migaud said they supported the measure. Whether it will be possible to change the law amid the political turmoil gripping France is another matter. There is good-faith debate among feminists and legal experts about whether enshrining consent in our definitions of rape will bring more justice to victims in practice. Spain’s experience shows that such laws must be drafted carefully — the introduction of the “only yes means yes” law led to some perpetrators having their sentences reduced on appeal. What is clear is that the justice system as it stands fails victims of sexual assault to the extent that rape is effectively decriminalised in this country, and that this must change. Gisèle Pelicot, who has suffered more than many of us could imagine, has used her suffering to change the world for the better. She turned what could have been an unedifying media circus into a masterclass of ordinary dignity that carries a powerful and subversive feminist message. She has shed light on a culture of normalised sexual abuse that has traditionally been minimised and recategorised as a national commitment to flirting and love. In Avignon, she told the court: “It’s true that I hear lots of women and men who say, ‘You’re very brave.’ I say, ‘It’s not bravery, it’s will and determination to change society.’” Against the odds, she has done it.  New here?Impact is a weekly newsletter of feminist journalism, dedicated to the rights of women and gender-diverse people worldwide. This is the English version of our newsletter; you can read the French one here.  Do you love the Impact newsletter? Consider supporting feminist journalism by making a donation!

|

Inscrivez-vous à la newsletter gratuite Impact (English) pour accéder au reste de la page

(Si vous êtes déjà inscrit·e, entrez simplement le mail avec lequel vous recevez la newsletter pour faire apparaître la page)

Nous nous engageons à ne jamais vendre vos données.